Your cousin shares a family tree with 47,000 people. Your researcher friend has 200 ancestors, each documented with 12-page case files. Who's doing genealogy the "right" way? The answer may surprise you: both approaches have legitimate value—and the debate reveals more about your goals than about genealogy itself.

In This Article

The digital age transformed genealogy from meticulous library work to AI-powered hint machines. Unlike typical "be accurate" advice, this article explores why quantity can lead to quality, why even poorly-cited research contains valuable original content, and how to define success on your own terms.

The Evolution: From Card Catalogs to AI Hints

Before the internet, family history research demanded extraordinary dedication. Researchers spent years traveling to courthouses, writing letters to distant relatives and churches, and planning research trips to gather information. Making connections with other family historians pursuing related histories represented some of the most rewarding experiences—but these connections happened infrequently.

The internet changed everything. Records that previously required physical searches are now available online. Modern genealogy platforms develop tools that "come to you with suggestions"—you enter your tree, and the system proactively suggests potential matches, DNA connections, and other researchers working on similar families.

The Mega-Tree Phenomenon

For experienced, technology-savvy researchers, accessing these mega-collections of digitized records can be remarkably rewarding—at least in terms of building expansive family trees. A mega-tree containing thousands of individuals can emerge in weeks rather than decades.

If you're pursuing a mega-tree, modern tools are your ally. If you're not sure whether that's your goal, it's worth pausing to ask: what exactly are you hoping to create as the product of your genealogy efforts?

The Citation Conundrum: Is Unsourced Data Worthless?

The genealogy community seems conflicted on this subject. On one hand, new records and online sharing create enormous opportunities to learn things that would otherwise take much longer—or be impossible—to discover. On the other hand, this same technology propagates inaccurate and even "borrowed" content at lightning speed.

One thing should be clear: anyone using another researcher's work should cite it properly. If you use publicly available information, proper attribution is appropriate. If you use substantial portions of someone else's work, permission may be required. Beyond the rules is practical logic—if you wish to retrace your steps later, citing sources saves enormous time.

Don't Throw the Baby Out With the Bathwater

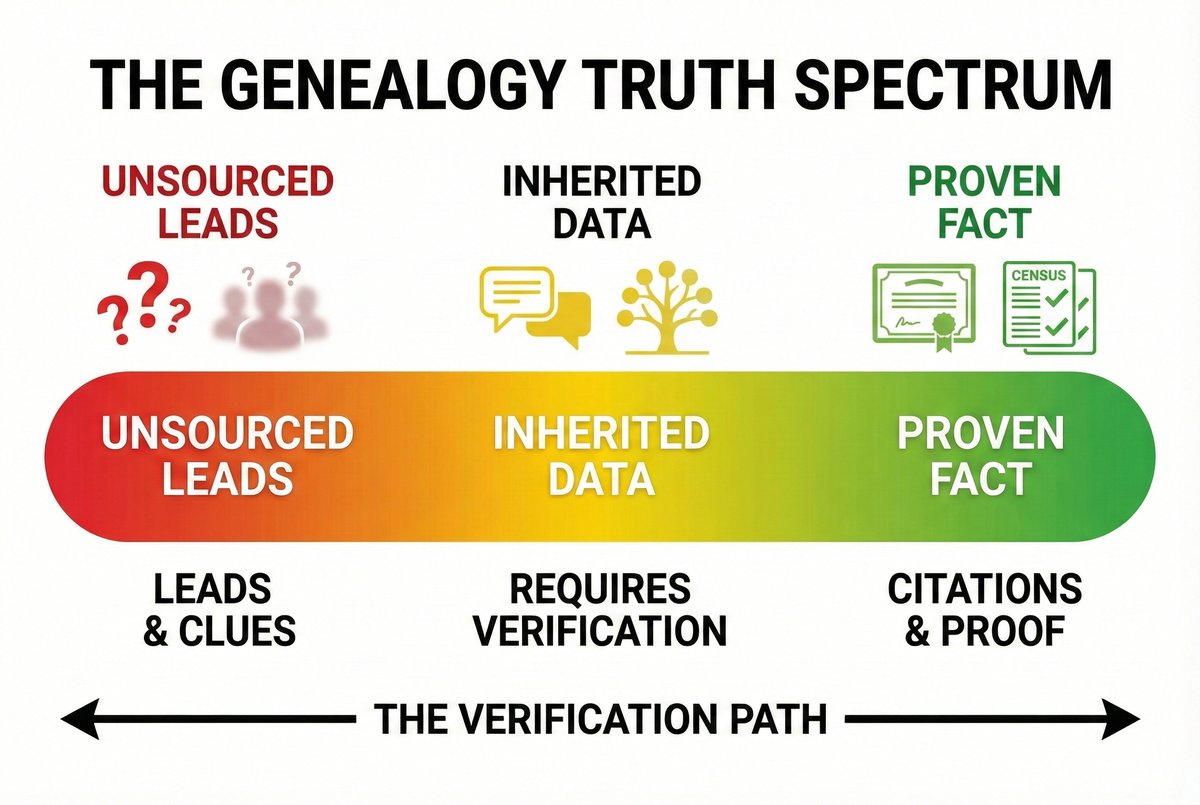

With proper citation chains, determining information credibility becomes feasible. But here's the question each genealogist must answer: if the citation chain is broken in some or all items in a collection, does that make the information useless?

Some genealogists advocate a strict approach: if sources are missing, discard the data entirely. We take a different view. Even work that lacks proper citations probably contains nuggets of original content gleaned from family members, personal knowledge, and firsthand experience. That's often how genealogy research begins—and such information represents valuable primary source material.

Unsourced doesn't mean useless—it means unverified. Treat inherited research as leads requiring verification, not facts requiring deletion. Use unsourced trees to identify what records to search for, then do the verification work yourself.

The Quantity-to-Quality Path: When More IS Better

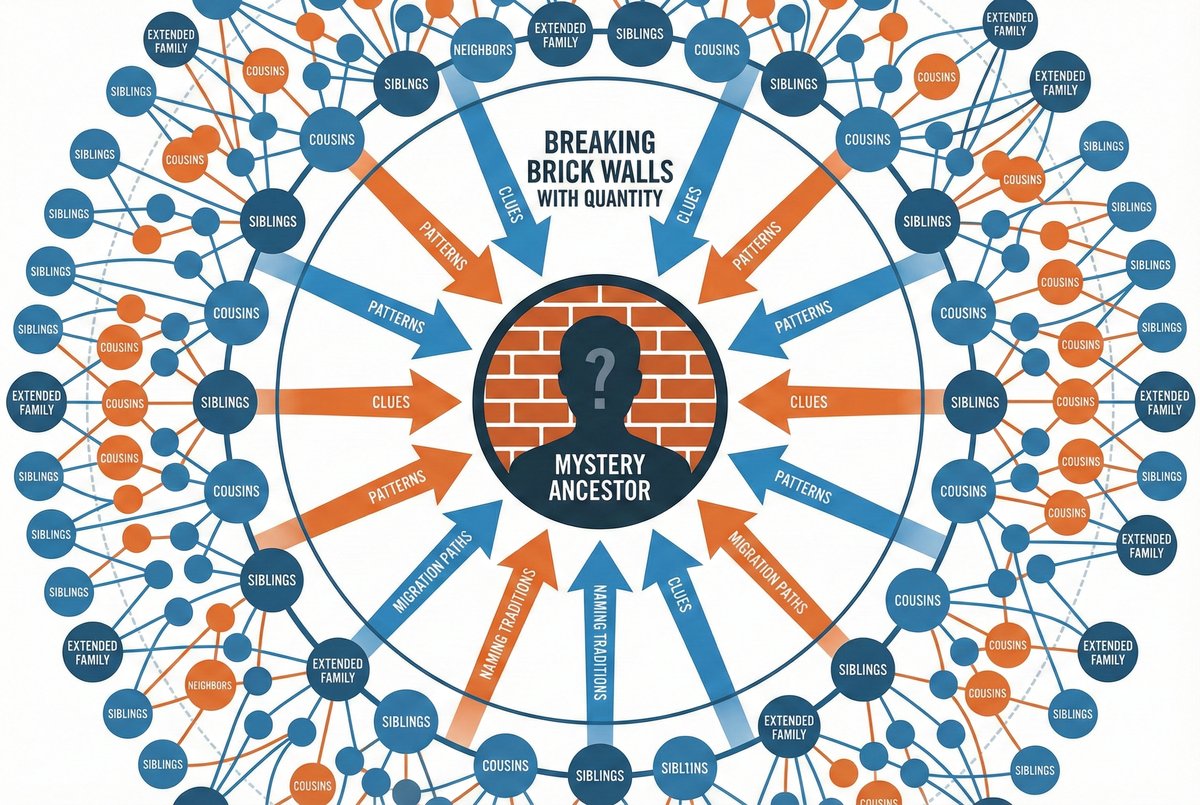

There's a strong tendency among genealogists to pursue only direct ancestral lines. Our experience suggests this approach misses valuable opportunities—much information about direct lines comes from researching indirect relatives.

Consider the power of collateral research: studying your ancestors' siblings, cousins, and extended family networks. When you're stuck on a brick wall ancestor, researching 40 collateral relatives often reveals patterns that break through. Naming traditions, migration paths, occupational patterns, church affiliations—these become visible only with volume.

More information than many researchers know what to do with is now available. Take your time with it. Search for the best information available. Don't discard things just because some items within are questionable—but also don't accept information at face value.

Making It Matter: The Accessibility Challenge

Here's a paradox many genealogists discover: you can build an impressive 10,000-person tree, yet struggle to get family members interested in it. We've been surprised by how difficult it is to engage people with their family history—even when it's handed to them completed.

Perhaps the attraction is the quest itself, or perhaps the finished work is uninteresting, difficult to understand, or overwhelming. Tool builders have made efforts to help—automated charts, interesting facts, location data, timelines. But none of this changes the fundamental reality: it's up to the historian to make the history interesting.

This is why the quality vs quantity debate can miss the point. Quality of research and quality of presentation are different skills. A meticulously sourced tree that nobody reads has different problems than a sprawling mega-tree with engagement challenges. Both need work—just different kinds.

Finding Your Balance: Defining Success

There's no universal "right way" to pursue family history. What matters is aligning your approach with your actual goals.

Ask yourself:

- Are you solving a specific mystery? Depth and verification matter most.

- Building family connections? Breadth plus compelling stories create engagement.

- Contributing to genetic genealogy? Collateral volume helps match analysis.

- Preserving family knowledge? Quality documentation plus accessibility serve future generations.

The good news: you can change modes. Start broad to understand the landscape, then zoom in on lines that interest you. Shift between quantity and quality phases as your understanding evolves.

Quality Control in the Modern Era

Modern tools can help with both quantity and quality. Validation features identify inconsistencies. Collaboration tools let multiple researchers contribute while maintaining standards. The key is using technology to serve your goals rather than letting the tools define them.

Quality control doesn't mean starting over—it means building systematically on what exists, improving incrementally, and documenting your verification work so others (including your future self) can trust your conclusions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I delete my family tree if it has unsourced information?

No! Unsourced information remains valuable as research leads. Instead of deleting, mark uncertain data clearly and gradually verify it. Think of your tree as a living research document, not a published book. Improvement happens over time.

What's the minimum citation standard for shared genealogy?

At minimum, distinguish between what you personally verified and what you inherited from others. Cite secondary sources honestly—even "from Aunt Mary's research, 1987" preserves valuable provenance. Future researchers (including you) need to know the origin of each claim.

How many ancestors should I research before going deeper?

There's no magic number, but collateral research often breaks brick walls. When you're stuck on one ancestor, research their siblings and families. A good starting rule: for any ancestor you can't verify, research their entire immediate family network.

Is it worth building a large tree if my family doesn't care?

Consider the future—your work may matter to grandchildren you haven't met yet. But also refocus on stories, not just data. Even the best-documented mega-tree needs narrative hooks to create engagement. The goal isn't just accuracy; it's creating something people actually want to explore.

Summary

- Both approaches have value: Mega-trees and deeply-sourced research serve different legitimate goals

- Unsourced doesn't mean useless: Treat inherited research as leads, not facts—verify rather than delete

- Quantity enables quality: Volume reveals patterns; collateral research breaks brick walls

- Define your own success: Your goals determine your standards, not genealogy gatekeepers

- Accessibility matters: Quality research that nobody reads has different problems than broad research

- Improve iteratively: Start where you are, document your progress, enhance over time

Find Your Balance

Whether you're building your first mega-tree or citing your 500th census record, GenConverse helps you understand what you have and identify where to focus. Our validation tools help maintain quality as your research grows, and our conversational interface makes exploring your family data accessible to everyone. Try Genie to see your family tree from a new perspective.